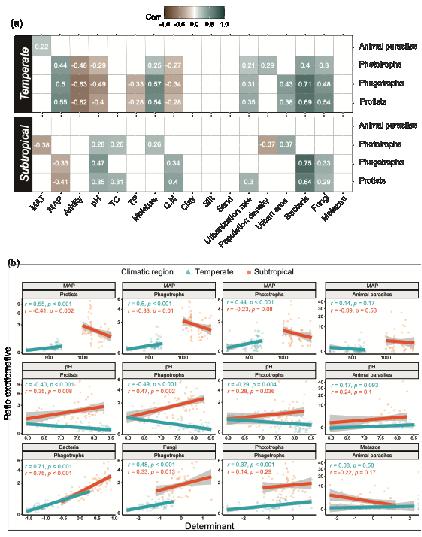

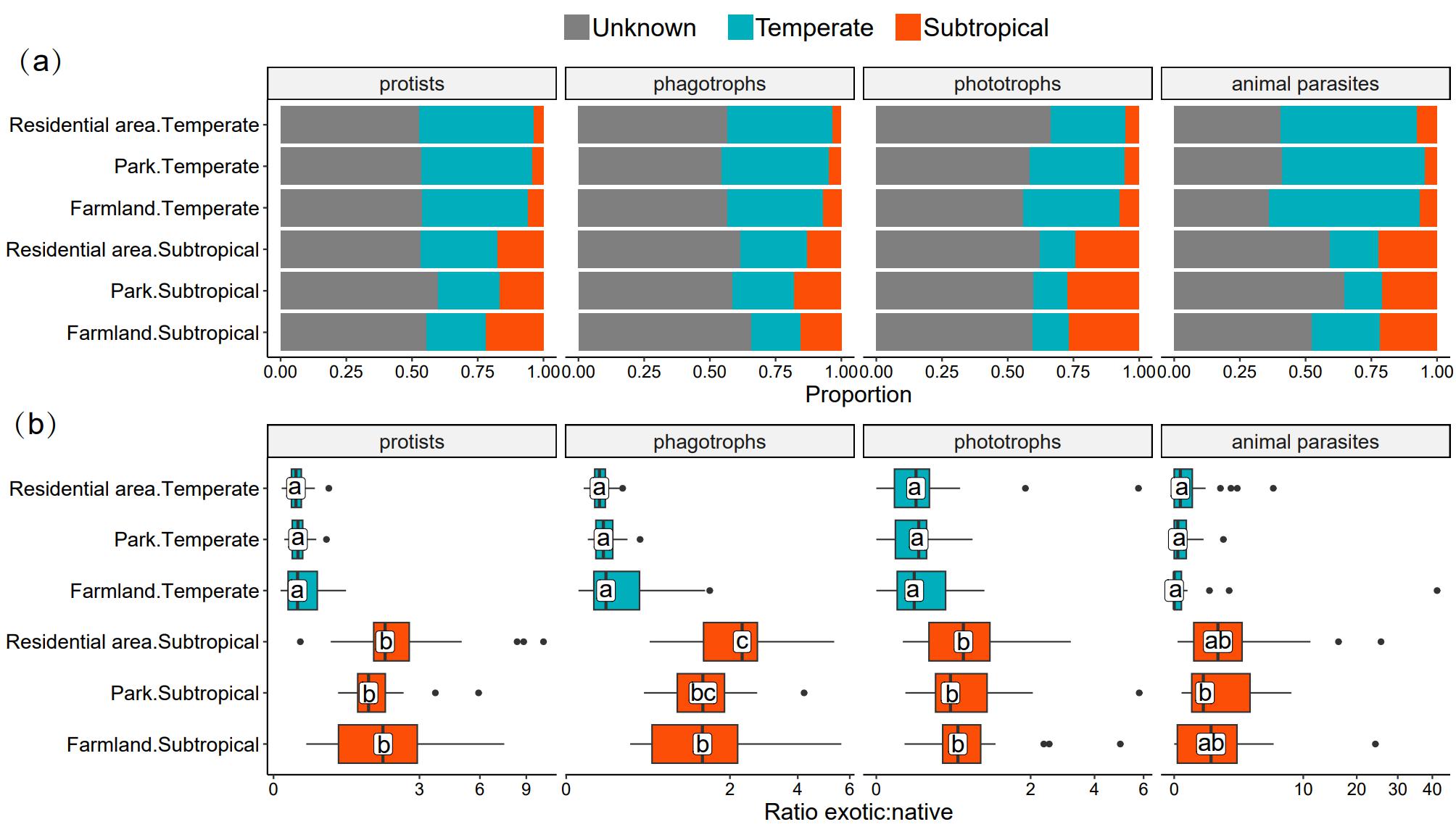

Land-use changes are reshaping the distribution of aboveground species worldwide. However, the impact of land-use changes on the distribution of soil organisms remains poorly understood. In particular, we lack a mechanistic understanding of the environmental factors reshaping the distribution of soil microbiota in response to global biological homogenization. Here, we used metabarcoding to investigate the biogeography of protists and their relationships with prey and hosts in three human-dominated ecosystem types, i.e., farmlands, residential areas, and parks, along with natural forests, in subtropical and temperate climatic regions across China. We found that human land-use systems extended the distribution range of habitat-generalist protists compared to forests. This human-facilitated spread of protists was highly directional and mainly driven by temperate to subtropical range expansion of soil taxa. Put simply, increases in soil pH associated with human land uses mitigate the natural acidity barrier typically found in subtropical ecosystems, facilitating the temperate to subtropical range expansion of protist species. However, in temperate regions, the northward expansion of subtropical species is likely restricted by a more arid climate with even higher soil pH. The cross-region spread of soil protists was more pronounced in phagotrophs than phototrophs and parasites, reflecting codispersal of phagotroph protists and microbial prey (especially bacteria) related to tight predator–prey specialization and/or similar responses to environmental changes. Our findings indicate that land-use changes create hotspots of potential microbial invasions, particularly in subtropical and tropical regions, highlighting that understudied regions are likely to be strongly affected by biological homogenization related to introduction of exotic species.